If music be the food of love, then where better to dine out than a world-class concert hall or opera house? Here, Architonic examines a number of recently completed architectural projects that perform as hard as the artists who take to their stages. Play on.

-

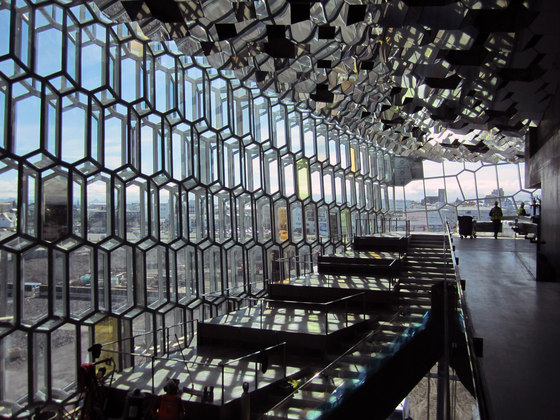

Henning Larsen Architects' new Harpa Concert &

Conference Centre was conceived of as part of Reykjavik's

harbour-development project; photo © Osbjørn Jacobsen

-

Given the digital times in which we live, there's

something reassuring about the fact that intelligent, relevant and

inspiring performing-arts venues are still managing to be designed and

built. In all their glorious materiality, they cock a cultural snook at

the ever-growing disembodied consumption of online and downloaded music,

dance and other art forms.

-

-

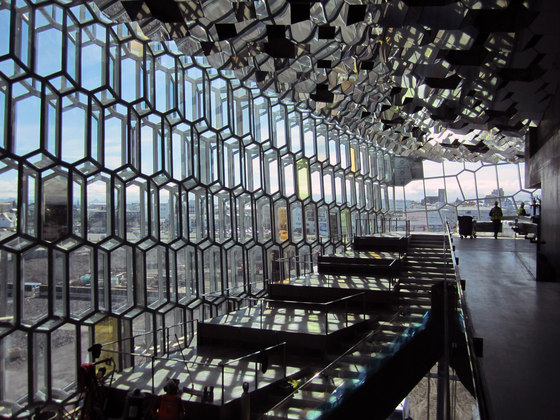

The architects collaborated with celebrated

Danish-Icelandic artist Olafur Eliasson, whose striking 'quasi-brick'

glass façade exploits the natural light of the building's location to

produce a dynamic play of colours; photo © Osbjørn Jacobsen

-

Perhaps its a hard-wired social desire that we, as humans,

have to congregate and experience performance en masse and unmediated,

or maybe it has something to do with the perceived value of such

buildings in terms of the cultural profile they can lend a city (and the

economic benefits that often attend this), but, whatever the reasons

for their continued need, a number of architects are ensuring that newly

commissioned concert halls, opera houses and cultural centres in

general are as performative in terms of their design as the activities

they house.

-

The main auditorium at the Harpa Concert & Conference Centre; photo © Osbjørn Jacobsen

-

In terms of timing, there's something both unfortunate and

so right about Reykjavik's sculptural new Harpa Concert &

Conference Centre, designed by Henning Larse Architects. On the one

hand, completing such a costly project at a time when Iceland's economy

(and domestic politics) are in crisis, following the collapse of all

three of its national banks, is at best foolhardy and at worst

unaffordable. (Already underway when the national finances took a

nose-dive, the project was, of course, a hostage to temporal fortune to a

large extent.) But on the other, a landmark public project such as this

one might just have the symbolic capital to play a part in restoring

national pride and hope, much in the way that the 1951 Festival of

Britain, held at a time of great austerity, did with its future-gazing

architectural visions of modernity.

-

-

The Wexford Opera House, a collaboration between the

Irish state's Office of Public Works and London-based Keith Williams

Architects, whose visibility increases the further away from it you are;

photos Ros Kavanagh

-

The defining feature of the 29,000-square-metre Harpa,

conceived of as part of Reykjavik's harbour-development project, is its

striking façade treatment, the result of a collaboration between the

architects and Danish-Icelandic artist Olafur Eliasson, known for, among

other works, his large-scale 'The Weather Project' installation at

London's Tate Britain in 2003. Engineered by Rambøll and ArtEngineering

GmbH, the skin of the building takes a cue from nature for its design:

thanks to the building's exposed location, the reflective potential of

its outer surfaces is maximised, as light interacts with its

basalt-crystal-inspired geometric pattern to produce a dynamic play of

colours, particularly on the south-facing façade, which is composed of

over 1,000 of Eliasson's 'quasi bricks'. It comes as no surprise,

perhaps, that a country so readily identified (at least abroad) with its

unique landscape should rely on the physical natural context of such an

iconic architectural project to lend it character and distinction.

-

-

Horseshoe-shaped balconies in the main auditorium bring

visitors closer to the action, while encouraging people-watching. The

entire space is clad in walnut, a material also used generously in the

foyer (above); photos Ros Kavanagh

-

If the Icelandic project is all about the façade, then the

Irish coastal town of Wexford's opera house, the result of a

collaboration between the architectural practice of the Office of Public

Works (an Irish state agency) and London-based Keith Williams

Architects, is more a case of partial concealment. The literally named

Wexford Opera House, which was delivered on a budget of €30 million and

enjoys the status of Ireland's first fully specified, purpose-built

venue for opera, replaces the old Theatre Royal, which had been the

venue for the annual Wexford Opera Festival since 1952. In

contradistinction to Harpa, the Wexford project adheres to the adage of

modesty being the best policy. At street level, the structure chooses to

hide behind a row of reinstated period houses, while its fly tower is

visible only from a number of distant viewpoints. Like some kind of

Italo Calvino invisible city, the closer you get to this building, the

more it disappears.

-

-

Frank Gehry's New World Center in Miami Beach, Florida,

features an 80-foot-high glass curtain wall and giant LED screen on the

exterior, while inside the auditorium sail-like

acoustic-panels-cum-projection-screens animate the space; photos Claudia

Uribe

-

Inside is a main auditorium that seats 780 persons, while a

smaller, multi-purpose performance space accommodates an audience of

175. Traditional horseshoe-shaped balconies in the auditorium bring

visitors closer to the action, while, according to the OPW, 'enhancing

the “people-watching” opportunities', and the entire space is clad in

walnut. The acoustics arm of Arup were responsible for optimising the

sound performance of the hall for opera, while taking other art forms

into consideration. It may be all softly spoken on the outside, but,

inside, the Wexford Opera House makes sure it gets heard.

-

Gehry's signature tumbling forms define the foyer of the

New World Center, home of the New World Symphony; photo Claudia Uribe

-

From the Irish coast to Miami Beach. Architect Frank

Gehry's New World Center, a purpose-built home for the New World

Symphony and the grand master's first commission in Florida, meets

Wexford's use of traditional materials with high-tech capabilities. The

message that this project is 'state of the art' is communicated to

visitors before they've entered the building: an 80-foot-high glass

curtain wall on the east façade allows views into the structure's

interior, with its Gehry-signature cascading forms, and is continued

horizontally with a 650-square-foot LED light field, which performs the

dual function of providing high-visibility branding and announcing the

venue's programming. If Harpa seeks to foreground its façade and the

Wexford Opera House performs a partial concealment of its exterior, then

the New World Center, with its glass wall, points towards a

now-you-see-it-now-you-don't exterior treatment, whose effect is

heightened at night when internal illumination at night makes the façade

'disappear'.

-

-

Downtown-Athens' Onassis Cultural Centre uses linear

pieces of Thassos marble to construct its façade, which, depending on

how close or far away you are from it, appears opaque or

semi-transparent; photos © Nikos Daniilidis

-

The 756-seater performance hall continues the emphasis on

technology. Dual purpose can be found again, this time in the form of

the large, 360-degree 'sails' that span the upper half of the space,

which function both as acoustic panels, but also double as screens onto

which commissioned films and contextual information can be projected

from 14 different 30,000-lumen projectors. Sensory overload or a

heightened 'concert-going experience', as the architects put it? You

decide.

-

-

Designed by AS.ARCHITECTURE-STUDIO, the Onassis Cultural

Centre contains a 900-seater opera house/theatre, a 200-seater

conference hall/cinema, plus an open-air amphitheatre; photos © Nikos

Daniilidis

-

Greece, like Iceland, is a country that's found itself in a

less that advantageous position financially of late. Against this

socio-economic backdrop, AS.ARCHITECTURE-STUDIO's downtown-Athens

Onassis Cultural Centre, completed at the end of last year, functions

as, among other things, an expression of the cultural wealth the country

possesses. Built for the Alexander S. Onassis Foundation, the venue –

which contains a 900-seater opera house/theatre, a 200-seater conference

hall/cinema, an open-air amphitheatre, also seating 200 seats, as well

as a library, restaurant and exhibition hall – the structure references

classical antiquity in the most contemporary of ways. It consists

essentially of a Thassos-marble skinned volume on a glass plinth, the

building's façades constituted from a series of thin stone elements,

creating a simultaneous opacity and transparency, depending on how close

you are to the structure and on the level of internal illumination. The

marble membrane also serves as a screen for large-scale projection.

-

-

New York practice Diller Scorfidio + Renfro was charged

with transforming the Juliard School's Alice Tully Hall into a premiere

chamber-music venue. Its new glazed façade at street level replaces the

old opaque one; photos DSR (top), Iwan Baan (bottom)

-

But, of course, concert halls and opera houses are not

just about their exteriors. 'Musicians Hear Heaven in Tully Hall’s New

Sound', ran the congratulatory New York Times headline in 2009, as the

music community praised the acoustics of the newly redesigned Alice

Tully Hall, the Juliard School's concert space, originally completed in

1969 by architect Pietro Belluschi. Charged with reworking the venue,

while expanding the music school itself, renowned New York practice

Diller Scorfidio + Renfro addressed the part of the brief that called

for the transformation of the hall into a premiere chamber-music venue

by creating a partial 'box-in-box' construction that isolates the main

space from exterior noise (and the vibration from the subway). Thanks to

a new glazed façade at street level, which replaces the old opaque one,

the inner structure can also be seen from outside.

-

-

A partial 'box-in-box' construction isolates the main

space from exterior noise (and the vibration from the subway). African

moabi wood was used to line the auditorium throughout, giving it a

completely new set of acoustic credentials; photos DSR

-

Inside, a specially engineered African moabi wood was used

to line the auditorium throughout, giving it a completely new set of

acoustic credentials, while providing a visual unity that helps

audiences concentrate on the performance.

-

-

Intelligent lighting is used to direct concert-goers

intuitively from foyer to auditorium at the refurbished Frits Philips

Concert Hall in Eindhoven, Netherlands; photo Frank Tielemans

-

But if it's a true wall-to-wall treatment you want, look

no further than the Frits Philips Concert Hall in Eindhoven,

Netherlands, refurbished by Niels van Eijk and Miriam van der Lubbe. The

word 'Gesamtkunstwerk' comes to mind upon encountering the space, where

the interiors, furniture, staff uniforms and even the crockery were all

designed by the Dutch duo, in collaboration with Philips Ambient

Experience Design. But while the scheme might be a total one in terms of

the consideration that's been given to all its various elements,

there's still a subtlety about this project. Lighting, for example,

provides illumination (as is its utilitarian wont), but it also forms a

means of signposting the way from foyer to auditorium, leading guests

intuitively. The role of light, and by extension of image, in contrast

to the sound-making that takes centre stage at the Frits Philips Concert

Hall, is announced, moreover, in the new 13-metre-high angled glass

façade that the designers introduced into the front of the building, one

of the effects of which is to offer views into the foyer space.

-

-

The word 'Gesamtkunstwerk' comes to mind upon

encountering the Frits Philips Concert Hall, where Niels van Eijk and

Miriam van der Lubbe designed the interiors, furniture, staff uniforms

and even the crockery; photos Frank Tielemans

-

Van Eijk and Van der Lubbe's description of the Eindhoven

project's central idea as 'a meeting place', rather than just a concert

hall, underscores neatly what's at stake in all of these recent

performance-venue projects. For in these public spaces, it is the public

themselves, as much as the music professionals, who are on view.

Participation in live cultural events makes you feel, well, alive.

Connected. Now, that's got to be better than iTunes.